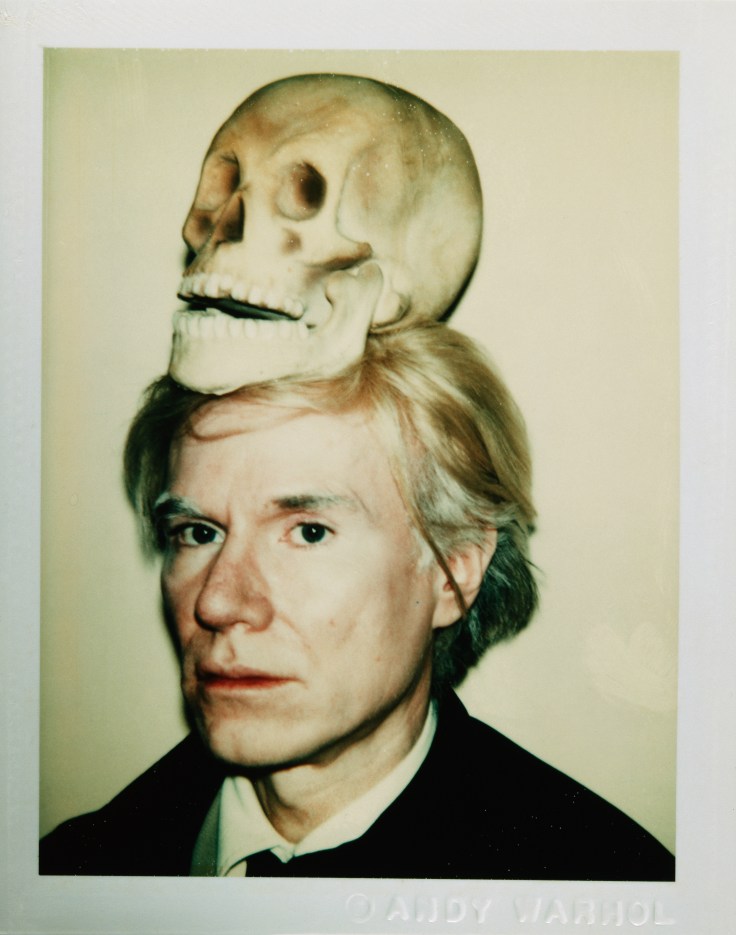

Thirty five years after his death, Andy Warhol remains a cultural icon and a purposefully enigmatic figure, whose expansive career took in painting, filmmaking, television, modeling, acting, co-founding Interview magazine, and various branded business enterprises. Far too often, his work and character continue to be misunderstood and dismissed as superficial, taking his comment from a 1967 interview too literally: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” Writer-director Andrew Rossi’s remarkable six-part docuseries, The Andy Warhol Diaries, executive produced by Ryan Murphy, determinedly examines what lies beneath that surface, using the pop artist’s posthumously published Diaries as a window into his personal life, thereby offering a rich and nuanced understanding of the man and his work.

Conceived as a way to keep track of his expenditure for tax purposes, Warhol’s Diaries quickly evolved to include details of all aspects of his life. They were dictated via telephone almost every week day at 9am, from November 1976 until his death in February 1987, to his friend Pat Hackett, who edited the published Diaries, condensing over 20,000 pages to around 800 in the process. In an interview for the series, Hackett describes the Diaries as Warhol’s “way of collecting his life”.

For Eva Hoffman though, in her original June 1989 review of the Diaries in The New York Times, the text was “almost entirely uninflected, and more endlessly repetitious than any of Warhol’s serial images”. She went on to question whether “Warhol’s voice” might have “got lost between dictation and transcription”, and concludes that “such a devotion to the spectacle of nothing” is “monumentally tedious”. However, she did acknowledge that were the “occasional glimmerings of a person” within the pages of the Diaries, and that Warhol “seems to get genuinely depressed by breakups with his boyfriends”.

With his documentary adaption of the Diaries, Rossi rediscovers “Warhol’s voice” and its “inflections”, with much of the series, ingeniously, narrated by Warhol himself. In a bold move that pays off beautifully, Rossi employs AI technology to build a vocal recreation—filtered through actor Bill Irwin—which sounds intentionally robotic at times, while at others affectingly human; alive with feeling and intention. When we first hear the AI Warhol, a caption on screen reminds us of his declaration to Time magazine in 1963: “Machines have less problems. I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” While later in the series, we witness Andy going through the uncomfortable process of modeling for a robot version of himself that’s being constructed.

Rossi also mines the Diaries for those “glimmerings of a person” and references to Warhol’s boyfriends. In fact, at the heart of the series is a sensitive, unhurried, and detailed exploration of the two most prominent and long-lasting romantic relationships in Warhol’s life. Firstly, the impossibly handsome Jed Johnson, whose introduction to The Factory in the 1960s saw him sweeping the floors, before going on to edit several Warhol movies, eventually directing Bad in 1977, then focusing on his own successful interior design career. After that relationship ended, Warhol began sending roses to a Paramount executive with movie star All-American looks, Jon Gould, and another enduring romantic partnership eventually developed, thanks to some matchmaking by Andy’s friend, the photographer Christopher Makos.

Endorsed by the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Andy Warhol Museum, the series creators had access to an extraordinary archive of film and video footage, photography, and of course artwork. In the segments that focus on Warhol’s love life, his own words are beautifully illustrated and enhanced by private photography, home videos (including a fabulous Cape Cod dinner), and letters and poetry between the men, that capture the intimacy and deep affection between them. Both Jed and Jon shared Warhol’s East 66th Street Manhattan townhouse with him during their respective years with the artist, and Warhol was introduced to their families. Rossi ponders whether, decades before equal marriage, Warhol would have considered both of these relationships as essentially marriages. He answers his own question with the wealth of evidence he offers us about how they shared their lives. One particularly touching detail is the amount of time Warhol spent at Gould’s hospital bedside, especially given the artist’s understandable fear of medical establishments, following the trauma of being shot in 1968.

The references in the Diaries to Jed and Jon are frequent, but fairly circumspect at times, and at one point Warhol mentions that Jon, who was not out in his professional life, had asked not to be named in them, with Andy coming up with the solution of using Paramount Pictures as a pseudonym. On occasion, when Warhol leaves out certain details about Jon which Hackett felt were pertinent, she inserts brief, matter-of-fact editor’s notes. All of which leaves plenty of detective work for Rossi to build a full picture of Andy’s romantic life, aided by valuable contributions from those who were there at the time, such as Jed’s twin brother Jay Johnson, and Hackett herself.

Another figure who loomed large in Warhol’s life while he was writing the Diaries, is the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, and equal time is given to the examination of the significance and complexities of their close relationship. There’s some captivating footage of the men at work on their painting collaborations, and a valuable reassessment of how Basquiat was treated by the art establishment and critics (derided as a “mascot” in The New York Times review of his 1985 exhibition with Warhol), and the impact that had on him personally and creatively.

Along with archive interviews, there’s an array of engaging, concisely edited contributions from Warhol’s surviving celebrity friends such as Jerry Hall, Debbie Harry, and Mariel Hemmingway, and those who worked closely with him. John Waters is particularly insightful and entertaining when discussing Warhol’s movies, while fellow artist Julian Schnabel, counters the perception of Warhol as a vampire who used his entourage of Superstars at the Factory, arguing instead that “he gave people enough room to be what they wanted to be”. In an effective, recurring visual motif, each present day contributor is introduced with a short Warhol style Super 8 screen test sequence. At times we hear sections of the Diaries, both in Andy’s voice, and echoed by contributors, with Rossi wisely bringing their focus back to Andy’s words and his version of events to either counter or align with their own recollections. Meanwhile, Brad Oberhofer’s dreamy, nostalgia-tinged score never manipulates, but subtly evokes each era and helps us to absorb the atmosphere conjured by Warhol’s words.

Some of the most intriguing commentary about the value of relating Warhol’s personal life to his art comes from Jessica Beck, curator at The Andy Warhol Museum. “No one wants to talk about Warhol having relationships that are important to his body of work, that he is using” she claims, “but I think that Warhol’s biography is important for some of the reading of the work, because this idea of intimacy or queerness is always there”.

While certain elements of the art world might be reluctant to examine Warhol’s output within the framework of his sexuality, Rossi presents us with a fully-rounded picture of the man, led by his art and words, that encompasses work that’s often overlooked, including unapologetically queer imagery from his oeuvre. Led by the Diaries, Rossi also explores Warhol’s lifelong relationship with Catholicism. According to Bob Colacello, former editor of Interview, Warhol’s mother would take him to vespers each Saturday and then three masses on a Sunday. Towards the end of the series, there’s a fascinating sequence devoted to Warhol’s epic swan song series, The Last Supper, which builds to a critical reexamination of the work through the lens of Andy’s queerness, the inescapable presence of “Gay Cancer”, and the judgment of those with loud voices like Jerry Falwell who preached that AIDS was God’s punishment. The AIDS crisis permeates the later episodes, taking in Andy’s fear of it and the horrific loss of life surrounding him in the 80s.

One of the most thrilling aspects of the series is the portal that the Diaries open to a bygone New York City. There are of course the socialite and celebrity parties, and the poetic glamour of entries like the evening that Diana Ross performed in the rain in Central Park in 1983, followed by Andy’s night out with Rob Lowe. Even more enticing though, is the series’ depiction of the queer scene during Andy’s decades in the city. At one point, the Diaries reference a night of gay bar and club-hopping with Studio 54’s Steve Rubell: “Stevie wanted to go to the clubs…the Cockring over on Christopher Street…we went to 12 West and I wouldn’t dance…then we went to Anvil for a minute”. This leads to one of the highlights of the first episode, an intoxicating, transporting time capsule of a sequence, brilliantly edited by Steven Ross at a pulsating pace, presenting us with a riot of queer imagery. We’re immersed in the gay scene of the late 70s and early 80s through a mix of images from Andy’s own work along with archival footage of the leathermen filled streets of the Meatpacking district, busy bathhouses like Man Country, and packed dance floors, including flashes of Friedkin’s Cruising (shot in real locations using regulars as extras), set to the throbbingly infectious late disco sounds of Sparks’ The Number One Song In Heaven. As writer, critic, and artist Lucy Sante observes though, Warhol didn’t fit into the gay tribes of the era, making him both an outsider in the city’s gay scene, as well as an observer with a front row seat.

Later, the Diaries tell us, Warhol would discover a love for dancing at Studio 54, largely in order to get lost in the crowd and to be left alone. Rossi finds a way to make the segments about that well-documented legendary nightclub feel new by leading us through Andy’s experience of it and using unfamiliar footage and photography, to the sounds of the ultimate queer disco icon Sylvester. As Andy spent an increasing amount of time both at 54 and outside it, with Victor Hugo (recently portrayed by Gian Franco Rodriguez in another Ryan Murphy project, Halston), a distance grew between him and Jed Johnson, who wasn’t part of that drug-fueled disco scene. The situation was exacerbated when Johnson discovered the vast amount of nude photographs of hustlers, porn performers, and bathhouse-goers that Warhol had taken for his Sex Parts series, with assistance from Hugo, which Andy refers to as “landscapes” in the Diaries. Refreshingly, throughout the series, rather than shying away from Warhol’s explicitly queer works, Rossi centres them, giving them equal significance and weight to the artist’s more ubiquitous and revered work.

At times Rossi lingers over the question of how out Warhol was, with archive footage illustrating that he often deflected media intrusions with answers that portrayed him as asexual. However, as artist Glenn Ligon observes, Warhol’s sexuality was an “open secret”, but he “was the right kind of gay”—unthreatening, not overtly political—he was “nice artist gay, acceptable”, which enabled him to keep his seat at the height of Manhattan society and maintain his businesses, especially during the heightened homophobia of the 80s.

The series isn’t a hagiography. In her consideration of The Last Supper, Jessica Beck references the criticisms that have been aimed at Warhol by some for not being the AIDS activist that his friend Keith Haring would become. While Rossi allows space for discussions about language in the Diaries that might through today’s lens be perceived as racist. Ligon also calls into question the potentially exploitative nature of the small fee Warhol paid to photograph the drag queens, trans, and gender nonconforming subjects of his Ladies and Gentleman series, such as Marsha P. Johnson, given the large sum that he was being paid for the commission. Less fruitful than others areas of exploration in the series, these segments nevertheless create a sense of balance, and leave room for debate.

Some of the most compelling and moving moments are Warhol’s succinct and illuminating meditations on life, like his sense of dissociation in the moment that makes TV and movies feel more real: “Your own life, while it’s happening to you, never has any atmosphere until it’s a memory”. Speaking of movies, it turns out that Warhol was a fan of Grease 2 (I knew he had good taste), and was deeply affected by The NeverEnding Story.

Following A Secret Love, Circus of Books, and Halston, Ryan Murphy continues his incredible run of supporting and creating untold queer stories at Netflix. A stunning achievement—expansive, yet intimate—The Andy Warhol Diaries penetrates deeply beyond the biographical. Both celebratory and investigative, uncovering Warhol’s romantic life with depth and delicacy. The mix of personal archive footage and photography, with Warhol’s own work, along with the personal correspondence, forms an intricately crafted collage that immerses us into his world and evocatively visualizes his words. While the AI voice rendering surprisingly leads to some moments that are poignant, even profound, ironically helping to humanize an icon, along with the candid images of him smiling and laughing. Rossi doesn’t seek to offer easy answers, acknowledging no one aspect of a character defines a person, allowing for a portrait as layered as one of Warhol’s multicoloured silkscreens. Over three decades after his death and the publication of the Diaries, this series offers a fresh perspective on Warhol, and a much-needed reexamination of his later works. The result is magnificent. This is essential viewing.

By James Kleinmann

The Andy Warhol Diaries premieres on Netflix on March 9th 2022.